"The heavens were overspread with black clouds; the winds unchained, raised the sea mountains high; terror again rode triumphant on the billow; dashed from side to side, now suspended betwixt life and death," M. Savigne

This is an excerpt from

THE BOOK OF-SHIPWRECKS, AND NARRATIVES OF MARITIME DISCOVERIES

Published by Charles Gaylord, Boston, 1840

The Wreck of the Medusa

In July, 1816, the French frigate the Medusa was wrecked on the

coast of Africa, when part of the ship's company took to their boats; and the

rest, to the number of one hundred and fifty, had recourse to a raft hastily

lashed together. In two hours after pushing

off for the shore, the people in the boats had the cruelty to bear away and

leave the raft, already laboring hard amid the waves, and alike destitute of

provisions, and instruments for navigation, to shift for itself. "From the moment," says M. Sevigne, from

whose affecting narrative this account is chiefly taken, “that I was convinced

of our being abandoned, I was strongly impressed with the crowd of dark and

horrible images that presented themselves to my imagination; the torments of

hunger and thirst, the almost positive certainty of never more seeing my country

or friends, composed the painful picture before my eyes; my knees sunk under

me, and my hands mechanically sought for something to lay hold on; I could

scarcely articulate a word. This state soon

had an end, and then all my mental faculties revived. Having silenced the tormenting dread of

death, I endeavored to pour consolation into the hearts of my unhappy

companions, who were almost in a state of stupor around me. No sooner, however, were the soldiers and

sailors roused from their consternation, than they abandoned themselves to

excessive despair, and cried furiously out for vengeance on those who had

abandoned them; each saw his own ruin inevitable, and clamorously vociferated

the dark reflections that agitated him." Some persons of a finer character

joined with M. Sevigne in his humane endeavors to tranquilize the minds of

these wretched sufferers; and they at last partially succeeded, by persuading

them that they would have an opportunity in a few days of revenging themselves

on the people in the boats. "I

own," says M. Sevigne, "this spirit of vengeance animated every one

of us, and we poured vollies of curses on the boat's crew, whose fatal

selfishness exposed us to so many evils and dangers. We thought our sufferings would have been

less cruel, had they been partaken by the frigate's whole crew. Nothing is more exasperating to the unhappy,

than to think that those who plunged them into misery, should enjoy every

favor, of fortune."

After the first transports of passion had subsided, the sole

efforts of their more collected moments were directed to the means of gaining

the land, to procure provision. All that

they had on board the raft, consisted of twenty-five pounds of biscuit and some

hogs heads of wine. The imperious desire

of self-preservation silenced every fear for a moment; they put up a sail on

the raft, and every one assisted with a sort of delirious enthusiasm; not one

of them foresaw the real extent of the peril by which they were surrounded.

The day passed on quietly enough; but night at length came on;

the heavens were overspread with black clouds; the winds unchained, raised the

sea mountains high; terror again rode triumphant on the billow; dashed from

side to side, now suspended betwixt life and death, bewailing their misfortune,

and though certain of death, yet struggling with the merciless elements ready

to devour them, the poor castoffs longed for the coming morn, as if it

had been the sure harbinger of safety and repose. Often was the last doleful ejaculation heard

of some sailor or soldier weary of the struggle, rushing into the embrace of

death. A baker and two young cabin boys,

after taking leave of their comrades, deliberately plunged into the deep. "We are off," said they, and instantly

disappeared. Such was the commencement

of that dreadful insanity which we shall afterwards see raging in the most

cruel manner, and sweeping off a crowd of victims. In the course of the first night, twelve

persons were lost from the raft.

"The day coming on," says M. Sevigne,

"brought back a little calm amongst us; some unhappy persons, however,

near me, were not come to their senses. A

charming young man, scarcely sixteen, asked me every moment, 'When shall we

eat?' He stuck to me, and followed me everywhere, repeating the same question. In the course of the day, Mr. Griffen threw

himself into the sea, but I took him up again.

His words were confused; I gave him every consolation in my power, and

endeavored to persuade him to support courageously every privation we were

suffering. But all my care was

unavailing; I could never recall him to reason; he gave no sign of being

sensible to the horror of our situation.

In a few minutes he threw himself again into the sea; but by an effort

of instinct, held to a piece of wood that went be yond the raft, and he was

taken up a second time."

|

| The Raft of the Medusa, Théodore Gericault, 1819 (The Louvre, Paris, France) |

The hope of still seeing the boats coming to their succor,

enabled them to support the torments of hunger during this second day; but as

the gloom of night returned, and every man began, as it were, to look in upon

himself, the desire of food rose to an ungovernable height; and ended in a

state of general delirium. The greater

part of the soldiers and sailors, unable to appease the hunger that preyed upon

them, and persuaded that death was now in evitable took the fatal resolution of

softening their last moments by drinking of the wine, till they could drink no

more. Attacking a hogshead in the center

of the raft, they drew large libations from it; the stimulating liquid soon

turned their delirium into frenzy; they began to quarrel and fight with one

another; and ere long, the few planks on which they were floating, between time

and eternity, became the scene of a most bloody contest for momentary

pre-eminence. No less than sixty-three

men lost their lives on this unhappy occasion.

Shortly after, tranquility was restored. "We fell," says M. Sevigne, "into

the same state as before: this insensibility was so great, that next day I

thought myself waking out of a disturbed sleep, asking the people round me if

they had seen any tumult, or heard any cries of despair? Some answered, that

they too had been tormented with the same visions, and did not know how to explain

them. Many who had been most furious

during the night, were now sullen and motionless, unable to utter a single word. Two or three plunged into the ocean, coolly

bidding their companions farewell; others would say. 'Don't despair; I am going to bring you

relief; you shall soon see me again.' Not

a few even thought themselves on board the Medusa, amidst everything they used

to be daily surrounded with. In a

conversation with one of my comrades, he said to me, 'I cannot think we are on

a raft; I always suppose myself on board our frigate.' My own judgment, too, wandered on these

points. M. Correard imagined himself

going over the beautiful plains of Italy.

M. Griflen said' very seriously, 'I remember we were forsaken by the

boats; but never fear, I have just written to Government, and in a few hours we

shall be saved.' M. Correard asked quite

as seriously, 'and have you then a pigeon to carry your orders so fast?'"

It was now the third day since they had been abandoned, and hunger

began to be most sharply felt; some of the men, driven to desperation, at

length tore off the flesh from the dead bodies that covered the raft, and

devoured it. "The officers and

passengers," says M. Sevigne, "to whom I united myself, could not

overcome the repugnance inspired by such horrible food; we however tried to eat

the belts of our sabres and cartouch boxes, and succeeded in swallowing some

small pieces; but we were at last forced to abandon these expedients, which

brought no relief to the anguish caused by total abstinence."

In the evening they were fortunate enough to take nearly two

hundred flying fishes, which they shared immediately. Having found some gunpowder, they made a fire

to dress them, but their portions were so small, and their hunger so great,

that they added human flesh, which the cooking rendered less disgusting; the

officers were at last tempted to taste of it.

The horrid repast was followed with another scene of violence and

confusion; a second engagement took place during the night, and in the morning

only thirty persons were left alive on the fatal raft. On the fourth night, a third fit of despair

swept off fifteen more; so that, finally, the number of miserable beings was

reduced from one hundred and fifty, to fifteen.

"A return of reason," says M. Sevigne, "began

now to enlighten our situation. I have

no longer to relate the furious actions dictated by dark despair, but the

unhappy state of fifteen exhausted creatures reduced to frightful misery. Our gloomy thoughts were fixed on the little

wine that was left, and we con templated with horror the ravages which despair

and want had made amongst us. 'You are

much altered,' said one of my companions, seizing my hand, and melting into

tears. Eight days torments had rendered

us no longer like ourselves, At length, seeing ourselves so reduced, we

summoned up all our strength, and raised a kind of stage to rest ourselves upon. On this new theatre we resolved to wait death

in a becoming manner. We passed some

days in this situation, each concealing his despair from his nearest companion. Misunderstanding, however, again took place,

on the tenth day after being on board the raft.

After a distribution of wine, several of our companions conceived the idea

of destroying themselves after finishing the little wine that remained. 'When people are so wretched as we,' said

they, 'they have nothing to wish for but death.’ We made the strongest remonstrances to them;

but their diseased brains could only fix on the rash project which they had

conceived; a new contest was therefore on the point of commencing, but at

length they yielded to our remonstrances.

Many of us, after receiving our small portion of wine, fell into a state

of intoxication, and then great misunderstandings arose.

"At other times we were pretty quiet, and sometimes our

natural spirits inspired a smile in spite of the horrors of our situation. Says one, 'If the brig is sent in search of

us, let us pray to God to give her the eyes of Argus,' alluding to the name of the

vessel which we supposed might come in search of us.

"The 17th in the morning, thirteen days after being

forsaken, while each was enjoying the delights of his poor portion of wine, a

captain of infantry perceived a vessel in the horizon, and announced it with a

shout of joy. For some moments we were

suspended between hope and fear. Some

said, they saw the ship draw nearer; others, that it was sailing away. Unfortunately, these last were not mistaken,

for the brig soon disappeared. From

excess of joy, we now sunk into despair.

For my part, I was so accustomed to the idea of death, that I saw it

approach with indifference. I had

remarked many others terminate their existence without great outward signs of

pain; they first became quite delirious, and nothing could appease them; after

that, they fell into a state of imbecility that ended their existence, like a

lamp that goes out for want of oil. A

boy twelve years old, unable to support these privations, sunk under them,

after our being forsaken. All spoke of

this fine boy as deserving a better fate; his angelic face, his melodious

voice, and his tender years, inspired us with the tenderest compassion, for so

young a victim devoted to so frightful and untimely a death. Our oldest soldiers, and, indeed, every one,

eagerly assisted him as far as circumstances permitted. But, alas! it was all in vain; neither the

wine, nor any other consolation, could save him, and he expired in M. Coudin's

arms. As long as he was able to move, he

was continually running from one side of the raft to the other, calling out for

his mother, for water, and for food.

"About six o'clock, on the 17th, one of our companions looking

out, on a sudden stretching his hands forwards, and scarcely able to breathe,

cried out, ' Here's the brig almost alongside;' and, in fact, she was actually

very near. We threw ourselves on each

other's necks with frantic transports, while tears trickled down our withered

cheeks. She soon bore upon us within

pistol shot, sent a boat, and presently took us all on board. We had scarcely escaped, when some of us

became delirious again; a military officer was going to leap into the sea, as

he said, to take up his pocket book; and would certainly have done so, but for those

about him; others were affected in the same manner, but in a less degree.

"Fifteen days after our deliverance, I felt the species

of mental derangement which is produced by great misfortunes; my mind was in a

continual agitation, and during the night, I often awoke, thinking myself still

on the raft; and many of my companions experienced the same effects. One Francois became deaf, and remained for a

long time in a state of idiotism. Another

frequently lost his recollection; and my own memory, remarkably good before

this event, was weakened by it in a sensible manner.

"At the moment in which I am recalling the dreadful

scenes to which I have been witness, they present themselves to my imagination

like a frightful dream. All those

horrible scenes from which I so miraculously escaped, seem now only as a point

in my existence. Restored to health, my

mind sometime recalls those visions that tormented it, during the fever that

consumed it. In those dreadful moments

we were certainly attacked with a cerebral fever, in consequence of excessive

mental irritation. And even now,

sometimes in the night, after having met with any disappointment, and when the

wind is high, my mind recalls the fatal raft.

I see a furious ocean ready to swallow me up; hands uplifted to strike

me, and the whole train of human passions let loose; revenge, fury, hatred,

treachery, and despair, surrounding me!"

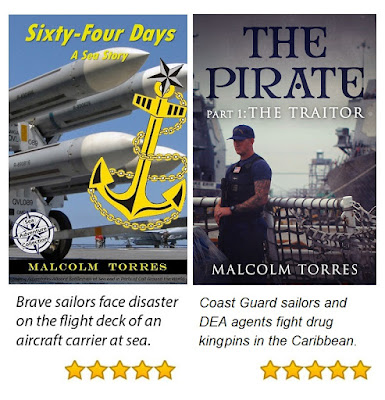

If you enjoy a good Sea Story . . .

these two salty tales are free on all eReaders:

Amazon Kindle, Apple iBooks, Barnes & Noble Nook, Smashwords and Kobo.

Malcolm Torres is the author and editor of sea stories and nautical fiction.

Connect with Malcolm Torres and keep the conversation going:

- Sea Stories And Science Fiction Podcast

- Sea Stories And Science Fiction Blog

- Malcolm Torres’ Books on Amazon

- Malcolm Torres’ Books on Apple iBooks

- Malcolm Torres’ Books on Barnes & Noble Nook

- Malcolm Torres' Book on Smashwords

- Malcolm Torres on Instagram

- Malcolm Torres on Twitter

- Sea Stories And Science Fiction YouTube Channel

- Sea Stories Book and Movie Review Playlist on YouTube

- Science Fiction Book and Movie Review Playlist on YouTube

#nautical #sailor #mariner #ship #sailing #seastory #lifeatsea #coastguard #shipyard #Navy #USN #USNavy #RoyalNavy #shipmate #seashanty #podcast #adventure #shortstories #booklover #booknerd #bibliophile #bookrecomendation #goodreads #greatreads #bookgeek #lovetoread #mystery #thriller #horror #crime #thriller #scyfy #sciencefiction #classicliterature #graphicnovel #novel #netflix #hulu #moviereview

Comments

Post a Comment